Robots edition

Whose embodied aesthetics are accepted as computable and worthy of credit in computing/engineering sectors?

This page details our first five-day residency at Brown University’s Humans to Robots Laboratory. With a particular emphasis on interrogating existing digital movement archives, we examine how Boston Dynamics’s Spot robots are already designed to embody dance.

Our methodology adapted tools and practices from dance improvisation and somatic practices that enabled critical intimacy while revealing the assumptions, limitations and power dynamics within the technological system.

Quick Links

Residency 1

•

Residency 1 •

These first moments spurred conversation about how we allocate agency, autonomy, and control onto the robot and the human controller.

How do we build mutual understandings of technical systems through applied learning in dance and robotics practices?

On our first day we established daily rituals for our collaborative process - grounding ourselves in shared practices as a group. We then spent the most of the day with a technical orientation of Spot - learning the different components of the system, how it is programmed to move around the space and how to navigate the system’s software and hardware.

This was Varsha, Jessica, and Elijah’s first time making the robot move. Varsha loved it. Jessica was skeptical. Elijah sat behind the desk.

1

2

3

4

Activities

Establish daily rituals to cultivate meaningful collaborator relationships

Create a research altar to hold meaningful items from each collaborator

Review Spot’s robotic system Spot Choreography SDK, Standard Operating Mode

Formalize safety protocols using robotic safety recommendations and theatrical communication safety protocols

How do we engage people who are wary of spot?

Day 1

First Contact:

What stood out

The group unpacked the cultural and technological implications of Boston Dynamics' Spot robot, particularly its role in dance and virality. Boston Dynamics initially received military funding for a humanoid robot project, which later led to viral dance videos that boosted the company's visibility. Tracing this lineage, we discussed how cultural capital has been acquired by dancing with Spot–noting that high-profile dancers like K-pop band BTS and Katy Perry have benefited from their robo-collaborations, which paint them as technologically connected and cutting edge.

Day 2

Deepening Understanding:

How does deepening our understanding of complex systems inform our awareness of their biases, rhetorical norms, and cultural impact?

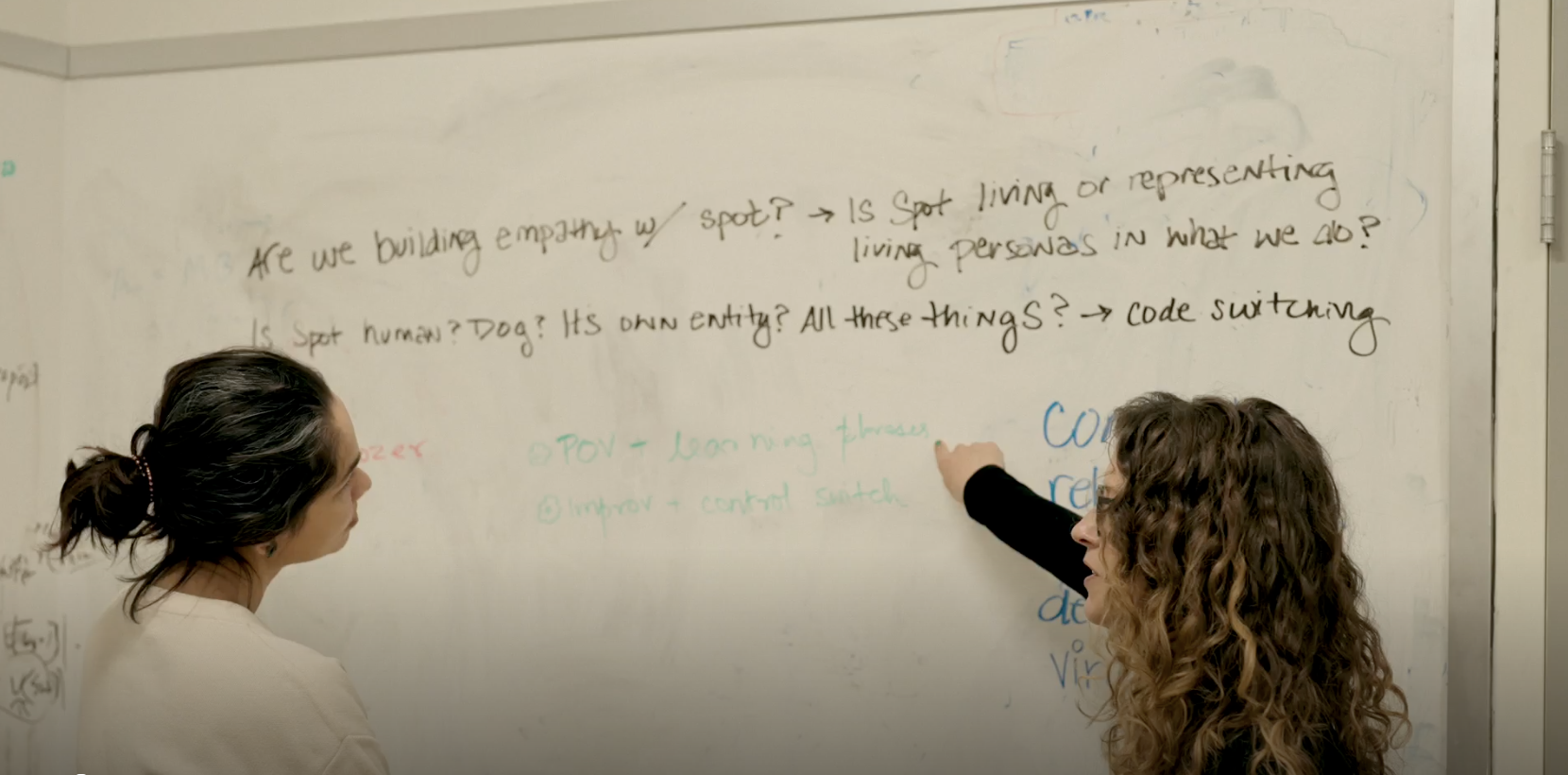

On our second day, we unpacked each of the major components that make up Spot’s robotic system and Choreography SDK. Through this process we discovered the ability for one controller to take robotic control away from another controller without asking permission. This is done through the “highjack” feature. Our discovery led to a rich discussion about the rhetoric of highjacking as it relates to power, agency, and control.

To explore further, we developed our first improvisational score to examine the feeling of highjacking. One person stands in the middle of a circle of other people. Someone standing around the circle says “me” and begins improvising movement. The person in the middle of the mirror turns toward the speaker and mirrors their movement until another person takes control by saying “me.” The person in the middle then turns toward the new controller and mirror’s their movement.

Hijack game

1

2

3

Activities

Deepen understanding of the different facets of Spot’s robotic system–Choreographer Interface, handheld controller, physical robot body, robotic sensing system

Develop an improvisational score where the team took turns operating Spot, as a way to understand control structures

Develop an improvisational score to embody Spot’s “highjack” feature

End of day

Our first improvisational score initiated our collective practice of embodying robotic system features toward a deeper awareness of how practical choices to support system efficiency and effectiveness are laced with rhetorically and behaviorally complex practices that carry very different meanings outside of robotic contexts.

Day 3

Embodied Connection and the Precarities of Humanizing Robots

How does tactile intimacy build embodied connection, and is embodied connection something we desire from robots?

As we transitioned back and forth between moving with each other and moving with Spot, we discussed the power and precarity of humanizing the robot.

As each of us moved Spot’s limbs, we used this terminology to articulate our experience, immediately noting that the passive motor resistance of Spot’s limb joints felt similar to gravitational pressure.

We questioned our own impulse to treat the machine with care and acknowledged that treating Spot as anything but a tool can be dangerous. Embuing Spot with human-like agency obscures the human control required to make the robot function—the humans controlling Spot are often hidden from view in viral videos to create an illusion of autonomy and robotic intelligence.

As we explored the robot, we wanted to build a more physical understanding of the robot. We powered off Spot and gathered around to explore the robot. To situate our experiences physically touching Spot within an improvisational framework, we utilized a touch-based improvisatory practice loosely titled Skin, Muscle, Bone.

1

2

Activities

Practiced an improvisational structure called Skin, Muscle, Bone

Spent time physically touching and moving Spot’s limbs while the robot is powered off

On the flip side, treating robots only as a tool felt equally insufficient–particularly in instances where robots are designed and marketed to be stand-ins for people. As we noted, robots are most often designed to do service work when created as stand-ins for people.

We used the sensation of gravity as a baseline to calibrate our touch, distinguishing between "skin" (light), "muscle" (medium), and "bone" (heavy) pressure.

How do we as interdisciplinary artists collaboratively translate our individual embodied histories into robotic code and movement, and what is lost (or found) in the retrofitting process?

Each team member choreographed their own movements — a historical dance, personal choreography, or movement exploration—and then attempted to retrofit them into the system using the movement available through the Spot Choreographer GUI. This process taught us that robotic movement is inscribed with the expertise, aesthetics, and embodied values of multiple people. We found that translating our movement onto Spot required us to negotiate practical, conceptual, and cultural shifts to "retrofit" our own movements into Spot’s robotic system.

Day 4

Collaborative choreography and Translation:

On the fourth day, we shifted to think about co-choreographing with Spot. To better understand our team's perspectives we worked with Bill T. Jones’s improvisational structure used in Floating The Tongue. We engaged with all Four Phases of the work. In Phase 3 and 4, we verbally described what we thought Spot was doing while performing choreographed movements. The process of listening to all the team members describe what Spot was doing gave us insight into the disciplinary, cultural, and personal biases we all have in relation to our work.

:

1

2

3

4

Activities

Review, Discuss, and Improvise with Bill T. Jones’s Floating the Tongue.

Review, Learn, and Dance and excerpt of Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A, a postmodern piece with a novel history of translation, citation, and performance.

Review, Learn, and Dance each team member’s speculative move.

Program each person’s speculative move onto Spot by using the existing Moves Library afforded by the Spot Choreographer GUI.

Grounded in this, we began the process of creating our Speculative Moves Library. We probed the system by creating a speculative process that responds back to the existing robotic library of motion [the Spot Moves Library], and Spot Choreography SDK.

Day 5

Synthesize and Debrief

We agree that documentation is vital. On our final day, we indexed on our Chunk and documented our experiences toward creating it. Creating “The Chunk” revealed that creating a singular, dancing body—human or robotic—requires multiple bodies to assemble, collaborate, ideate, and transpose their efforts onto the one form.

We realized we desire more transparency when dance is integrated into robotic design—not to assign blame, but to understand how decisions unfold over time. We spent the afternoon writing our personal rationale for each movement choice: Why did we select this move? What cultural or personal significance did it hold? How did we negotiate the translation? By documenting these choices, we created a library that reflected the specificity of the author's lived experience.

1

2

3

Activities

Create "The Chunk" by assembling individual movement contributions into a single, collaborative robotic phrase set to the voice recordings of team members speaking what Spot is doing. We did this by using Phase 3 and 4 of Bill T. Jones’s Floating the Tongue.

Document the origin, intent, and translation process of each move in our speculative moves library.

Debrief about our residency work, its impacts, and next steps.

“Individual dance identities are not singular in nature, but rather ‘an assemblage of multiple bodies’ terpsichorean motions.”